Who, what, why, where, when and how? If you’re struggling to find the right structure for your content, answering these six questions might be the key.

I’ll be honest, I hesitated to write this piece. Everyone knows the 5Ws and 1H, don’t they?

Then I remembered an experience in a client workshop that reminded me not to take for granted that everyone knows what I know.

Someone asked me, “What’s a CMS?” It’s a content management system, obviously. I spend half my life in one CMS or another… but, actually, why would they know that? They’ve never used one. They don’t work in communications.

So, in the same vein, I’m going to assume you didn’t study journalism and haven’t worked in content for years.

In which case, the 5Ws and 1H might be just the tool you need to make your content come together in a way that works for users.

This is the news

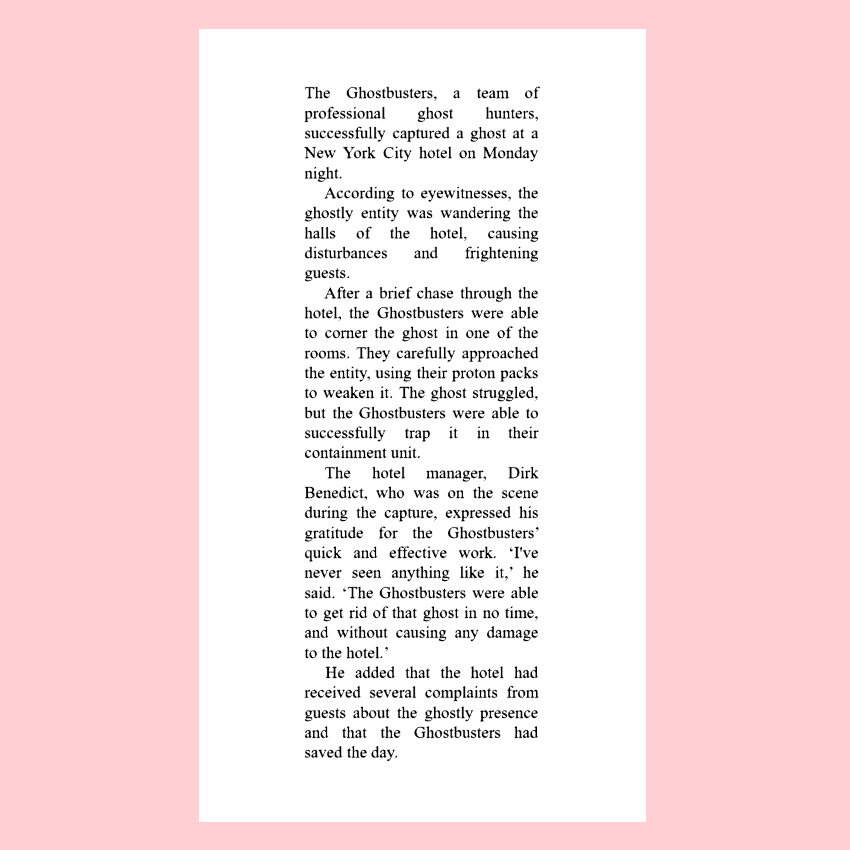

The 5Ws and 1H approach is the foundation that all good news stories are built on.

When you’re writing a new story, you want to tell the reader, in the first paragraph or two:

- who is involved

- what happened

- where it happened

- when it happened

- why it happened

- and how it happened

There’s no priority order and they’re not all relevant to every story, but you ask yourself all six questions every time, just to be sure.

This ties into something my colleague Miriam Vaswani wrote recently about how people take in information. As Miriam explains in that post, most people don’t carefully read each word, one after the other. They probably (1) skim, to work out if the article is relevant to them; then maybe (2) scan to pick out relevant details.

The 5Ws and 1H give those types of reader all the information they need right up-front. Then if they want or need to know more they can keep reading.

The inverted pyramid

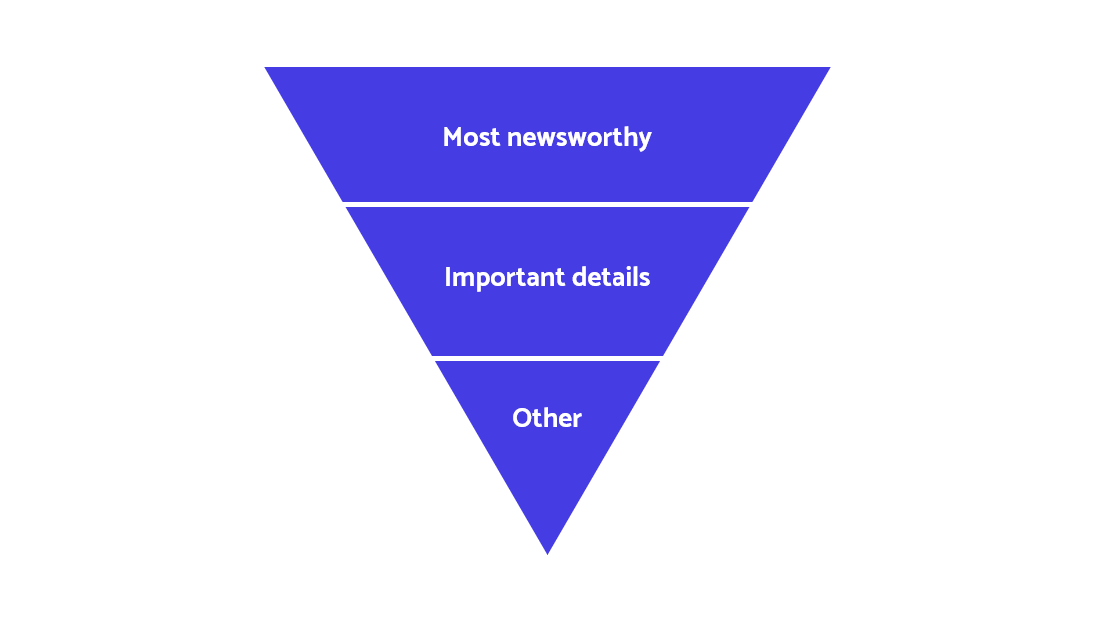

We usually combine the 5Ws and 1H with a principle called the inverted pyramid.

The idea is that the most important information goes at the top and is given most weight. This is the stuff most people will read.

We follow it with information of secondary importance. Quite a few people will read this, or at least skim or scan it.

Then the story goes into more detail for people who are really interested. This might be where you find quotes from eyewitnesses and background on the people involved.

Have a look next time you’re reading a news story and you’ll probably spot both the 5Ws and 1H approach plus the inverted pyramid in action.

They’re not used all the time, though. Opinion pieces and longform reportage often open with surprising statements (hooks), or evocative descriptions of people or places.

These aren’t rules, they’re tools.

Problem solving strategies

One great reason for talking about these classic journalistic techniques is that they can help us solve content design problems.

The reason they teach journalists these techniques is because they help us get past the difficult ‘blank page’ moment.

It’s also a great frame for content design – a way of restating the problem to engage our brains in a different way.

I heard a quote from a 2021 book called Framers on the Squiggly Careers podcast which makes the point well:

“The frames we employ affect the options that we see, the decisions that we make and the results that we attain. By being better at framing, we get to better outcomes.”

As content designers we can frame the problem by asking ourselves:

- Who is the user?

- What do they want to do, or need to know?

- Where do they need to go to get it? (Online, or in person.)

- Why should they do it? (What’s in it for them.)

- When can or should they access the service? (Opening times, availability.)

- How does it work?

Answering questions like these, tailored to the task or project, can cut through a lot of noise.

And applying the inverted pyramid can help us structure the information better.

What do they need to know most urgently? That’s probably your H1 (main header).

What’s least important? That might come towards the end, perhaps even after a link or button you want them to click, if it’s not essential for them to continue the journey.

In fact, you can also apply the inverted pyramid within individual paragraphs or sentences. It’s considered good practice in most cases to ‘front-load’ the most important information, with both legibility and accessibility in mind.

That’s why the Government Digital Service (GDS) recommends front-loading headings, titles and bullet points: “For example, say ‘Canteen menu’, not ‘What’s on the menu at the canteen today?’”

After a while, this becomes second nature to designers, but showing this thought process (showing your working) can help clients and stakeholders understand how you’ve made your choices.

I’ve also used the 5W and 1H approach to write meta descriptions, which appear in search engine results as page summaries. If you can get all the key information into less than 156 characters, users will be able to understand the purpose of your content and will be more likely to click through.

It’s also a useful way of organising content strategy documentation, such as email messaging – who needs to get an email, when, saying what, and so on – or content production workflows.

3 key takeaways

- If in doubt, ask who, what, why, where, when and how.

- Work out what’s most important and put it first.

- Show your workings to bring stakeholders on the journey.