In 2022, despite many attempts to solve the problem, inequality still exists in almost every organisation in the UK.

What this looks like in practice is…

- someone called Rawan still has to send 60% more job applications to get an interview than someone called Rob, with exactly the same CV;

- there are still more CEOs named John in the FTSE 100 than there are female CEOs;

- 4 in 5 autistic people are unemployed, as compared to 1 in 5 non-disabled people.

For all the books we’ve bought, workshops we’ve attended, training courses we’ve been on, and initiatives we’ve been a part of, not much seems to have changed.

There must be a better way.

Could the answer be creating a conversation that engineers real empathy at all levels?

Asking tricky questions

At the start of 2020, I met James Adeleke, CEO and founder of Generation Success. Generation Success is an award-winning social enterprise working to create a world where your career is not defined by the circumstances of your birth. The work they do is incredible, check out the Generation Success website to find out more.

James spoke to me about an initiative he had recently started called the Move to Equality Pledge. The pledge aims to address elitism, improve social mobility, inspire action, and enable all people to reach their potential. He hoped that organisations would sign up to the pledge, and it would act as a call to action for everyone within the business to create real change and provide equal opportunities for all young people.

I loved the idea! But I didn’t believe it would work. Because these initiatives never seem to work.

James’s response to me was to ask “why?” Why won’t this pledge, in particular, do the job?

That’s an excellent question. Why do people claim they want to make change happen, that they’re ready to do the work, but nothing gets done?

Why do we still have social and racial inequalities?

Despite it being completely illegal, why are some people treated differently because of their sex, gender, or race?

We know the business value of diversity. We know the benefits it brings to innovation, design, and the productivity of teams. And yet inequality and discrimination are rife across almost all sectors.

Well, I’m in the business of asking tricky questions. The way we answer them is to speak to the people affected, and use their insights to solve the problem in a way that directly answers their real needs. Why can’t we apply a human-centred design approach to solving this one too?

So that’s what we did.

We asked the questions:

- What are the real barriers to equality and inclusion?

- Why does inequality still exist?

- If we know what to do to create equality in our organisations and improve the diversity of the workforce, why are we still not doing it?

How we approached the problem

A small team from SPARCK, (me, Jimmy Adams and Abdur Rahman), led a series of user research focus groups to understand why equality initiatives might have failed in the past.

We wanted to speak directly to people who are affected by inequality in the workplace and understand their needs and challenges.

Between 29th July and 16th September 2020 we ran four moderated online focus groups with 27 participants.

We spoke to four distinct groups:

- Young talented individuals trying to break into industry. 16-24 year olds from lower socio-economic backgrounds, or people who have experienced racism.

- Diverse talent currently in industry but feeling excluded. 21-28 year olds who have been in industry for up to five years.

- Change makers. Individuals who have been in industry for more than eight years, who have experience of inequality and want to support this cause, but don’t know where to start; or those who have tried but failed in the past.

- Senior leaders. Senior executives and directors, including the then Minister for Business and Industry, Nadim Zahawi MP.

The aim of the research and the insights gathered was to design a set of resources that will support the Move to Equality Pledge, suggesting tangible actions grounded in the needs of the people it hopes to support.

We hoped to increase awareness of some of the issues facing individuals in the workforce, from those yet to enter through to the leaders who have the power to create change.

What we learned

One of the things that came out most strongly from the research was the number of microaggressions which are still perpetrated every day in offices across the UK.

A microaggression is defined by my pal Google Dictionary as “a statement, action, or incident regarded as an instance of indirect, subtle, or unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalised group such as a racial or ethnic minority”.

It might seem like a small thing, a micro thing, in fact.

Mispronouncing someone’s name. Speaking over someone in a meeting. Commenting on someone’s hair. Touching someone’s hair.

But they build up. They hurt. It’s “death by a thousand cuts”.

If we could stop them from happening, and help people understand their effect, we could create real change.

Why a game?

After months of research, I looked at the detailed research report we’d produced and thought, “nobody is going to read this.”

I felt we needed to make it practical, to build empathy with the struggle of individuals, so I designed a game.

The aim of the game is to put yourselves in the shoes of another.

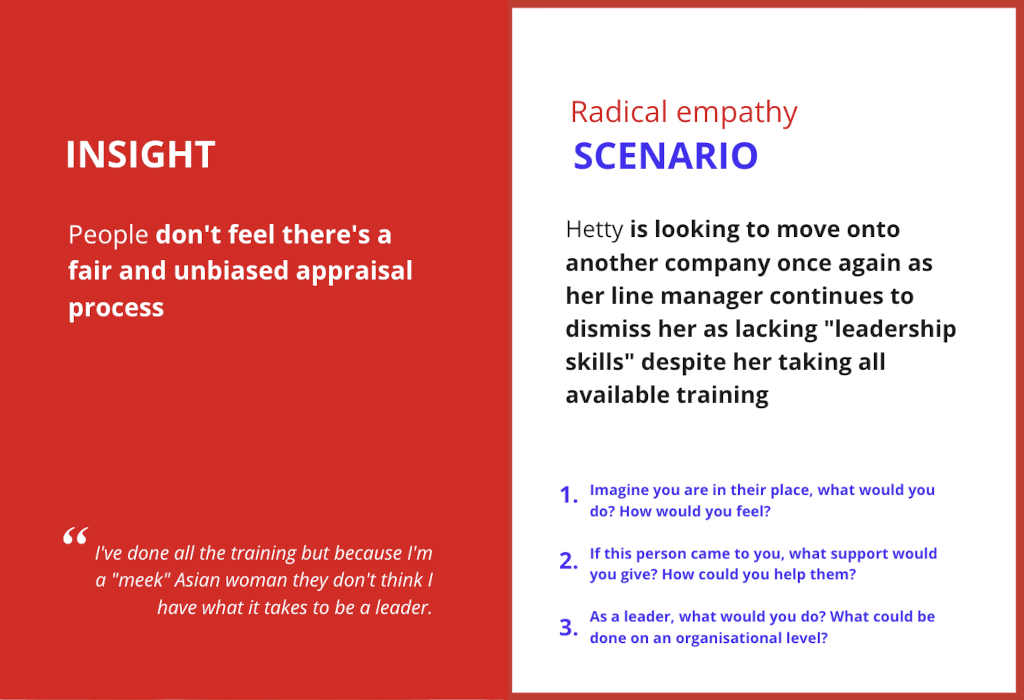

We took the hundreds of insights gathered from the research groups and, using the participants' real-life experience of inequality in the workplace, created anonymised, amalgamated scenarios.

Here are a few:

- Having been bullied for his name throughout school and college, Afamefuna now goes by the name Adam, to feel accepted and increase his chances of getting an industry break.

- Rikesh often feels compromised when his new work colleagues meet for after-work drinks as he doesn't drink alcohol but wants to make personal connections and not feel left out.

- Shanelle wants to be a senior leader one day but is dispirited as she has no role models from a similar background within the organisation to aspire towards.

We wanted to build awareness of others’ lived experiences and prompt an empathetic conversation about issues such as microaggressions, unconscious bias, and systemic oppression.

I know these are difficult subjects, but they only become more difficult to overcome if we ignore them and don’t have the uncomfortable conversations needed to change them.

We’ve run the game several times and each time I’m struck by the effectiveness of these deep, structured discussions.

As one participant put it:

“The biggest strength of this game is creating a safe space where we’re not afraid to be judged, and you get to speak with many different people. People who have experienced the scenarios as well as people who have the same questions as us. And even if we don’t have the answers to everything, reading the scenarios alone is already eye-opening.”

My underlying assumption within the game is that people aren't intentionally excluding others, but that is nonetheless the result of their actions.

Having these conversations will create a sense of psychological safety within our teams and make it easier to raise concerns and talk about issues if or when they arise.

Playing a game that no one wins

The game works at three levels, encouraging you to consider the various perspectives and levels through which inequality can be experienced, and tackled.

While playing you’re invited to take three perspectives:

- Imagine you are in the place of the individual who is suffering from inequality. What would you do? How would you feel?

- If this person came to you, what support would you give? How could you help them?

- As a leader, what would you do? What could be done on an organisational level to create positive change in relation to this scenario?

As you move through each of the perspectives, the aim is to empathise and consider the impact of the scenario not only on the individual but also on the community, and on the culture of an organisation.

No one wins the game, but everyone hopefully comes out of the conversation with a deeper level of empathy and an understanding of how their actions, regardless of intent, can affect every level of an organisation.

My personal takeaways

Having been a part of all of the research sessions and facilitated the game almost a dozen times, one of my biggest takeaways is how big-an-impact small, often unintentional actions can have on feelings of belonging and connection in an organisation.

We set out to solve the tricky problem of reducing inequality in organisations, and we uncovered examples of systemic and widespread discrimination that felt insurmountable. There’s a reason these issues still exist in the workplace today. A pledge won’t solve them, and a game won’t either.

However, by focusing on what we can each do on an individual level, as colleagues, managers and leaders, I believe that we can make the working lives of individuals better.

One of the reasons instances of micro-aggression still continue in organisations is because it takes a huge amount of emotional effort for an individual to confront someone. And their concerns can often be dismissed.

We captured that in a scenario based on our research: “Marjani regularly experiences microaggressions but fears telling her line manager as she'll likely say she's just misinterpreting other people's sense of humour.”

Take, for example, the common microaggression of mispronouncing, misspelling or abbreviating someone’s name.

It may be a small thing to you, and you may feel awkward in asking someone to repeat their name, but to that person it is a regular, and hurtful, signal that they are different, or a problem for you.

Not taking the time to learn how to pronounce someone’s name can make them feel as if they aren’t worth the effort, or as if their heritage, history, or identity aren’t respected.

Realising that I have personally done this several times was a huge moment for me.

In our research, several people spoke about actually changing their names completely so they would feel more accepted. That is terrible. That shouldn’t have to happen.

Change starts with awareness.

What this game does is allow us to have conversations about things like microaggressions in a safe space, without the need for confrontation or blame. Participants can begin to build a deeper understanding and empathy for the impact of their actions, reducing the likelihood of them continuing with behaviour that could make others feel excluded.

This game won’t solve all of our problems, but it’s a start.

As children we learn social skills through play. Maybe if we played more together as adults we’d learn how to treat each other better.

Do you want to try the game in your organisation?

Give me a shout if you want to know more and get hold of the resources you need to play the game yourself. You can email me or find me via LinkedIn.