As designers, we can use emotion to create better customer experiences. And we can map and even measure emotions, without compromising on rigour.

Like a lot of people at SPARCK, I got to a career in service design along a squiggly, winding path.

I started out with my degree in fine art photography before embarking on a five-year career as a wannabe rockstar in an indie band, touring the UK.

When I moved to Brighton, I realised I needed to get a ‘proper’ job. That’s how I fell into customer experience, strategy and design.

Since 2018, my job title has been ‘service design consultant’, but I’d argue I’ve been a service designer since 1993, when I first went to university.

What, even in the indie band period?

Yes, because at every stage of my career, I’ve been crafting customer experiences with intent. Even if those customers were in the front row at a gig, or shopping for records at Rough Trade.

What is service design?

Service design is about the user’s whole experience, not just a single touchpoint.

A UX designer might design a digital product, such as a single webpage.

A service designer, on the other hand, will think about that page in the context of the user’s whole life and the wider journey they’re on.

In an excellent 2021 article called ‘Service design – the what and why’ Renee Lin created a definition I really like:

“Service design is design for holistic experiences that happen over time and across different touchpoints, which aims to ensure a useful, usable and desirable service from customers’ point of view and effective, efficient and distinctive from service providers’ point of view.”

I also love how Renee visualises this: a Mickey Mouse doll is a product; the opportunity to meet and interact with Mickey Mouse at a Disney theme park is a service.

The service is all about how you’re treated from the minute you arrive at the park until the moment you leave, and even beyond and around.

Did you have an enjoyable experience? Do you remember it fondly? Or was it difficult for some reason, or stressful, or disappointing?

Understanding emotion is vital if you want to design services that work for users.

Humans are emotional

In a 2006 paper called ‘Once More With Feeling’ (PDF, MxDesign) Wade Lough cites Frank Luntz, a political consultant, who said:

“80 percent of our life is emotion, and only 20 percent is intellect. I am much more interested in how you feel than how you think. I can change how you think, but how you feel is something deeper and stronger, and it’s something that’s inside you. How you think is on the outside, how you feel is on the inside, so that’s what I need to understand.”

Having spent a lot of my early career working in customer experience I’d say, based on my experience, that split feels about right.

But back in around 2001, talking about emotions in that context was seen as ‘fluffy’.

I spent a lot of time in meetings trying to drive home the point made so efficiently by this poster from Smaply:

Things have got better since 2001 and businesses are more open to these ideas.

That’s partly because of advances in the science, from behavioural science to behavioural economics. We know more about the brain and how people make decisions, which is far from rational.

If science is embracing emotion, then that’s the evidence-based, green light that organisations need to get on board.

3 common mistakes in mapping customer journeys

To design good services, we need to map customer journeys, and the emotions behind them.

You could just map what the customer is doing, on the assumption that their choices are purely rational. But you’d be getting a poor, incomplete picture.

Think about someone trying to get help for a loved one who is bleeding heavily, for example. Or a person who has been locked out of their bank account and needs to buy a train ticket to get home for Christmas.

Reflecting on what they’re thinking and feeling, as well as their actions, is vital.

Another common mistake is using broad, generic language to discuss emotions: ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ are blunt tools.

And, finally, there’s the danger of making assumptions without ever putting them in front of customers.

In a perfect world, you’d co-create the map with customers. In practice, it’s fine to make assumptions as long as you validate them with customers, through user research.

To summarise, a good journey mapping session will:

- record the user’s actions

- consider their thoughts and feelings

- look at why they feel what they feel

- include the voice of the customer

Tools and techniques for designing emotions

The are many tools for mapping users' emotions, and designing those emotions into the experience.

I’m going to pick one example: the dramatic arc.

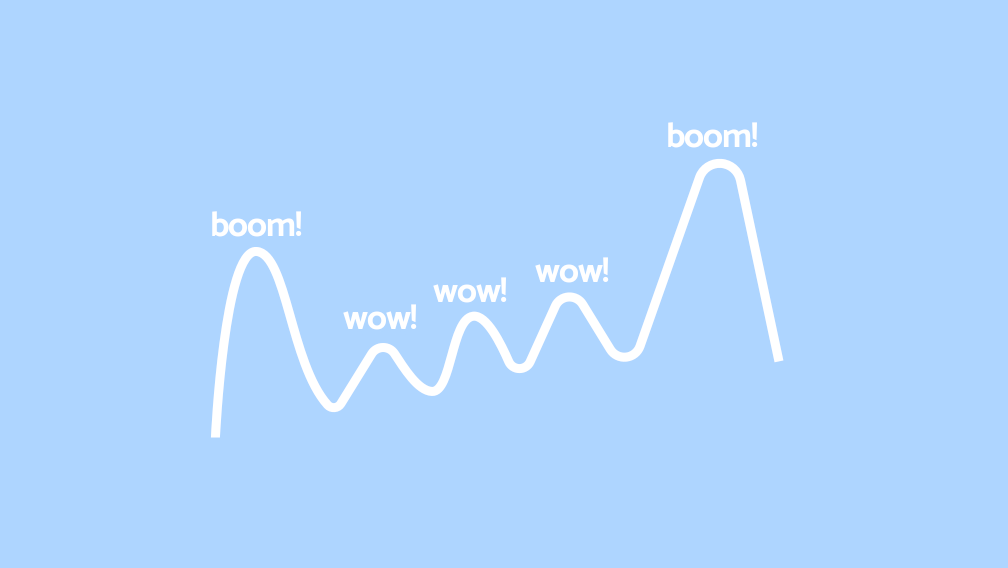

It’s sometimes also referred to as boom, wow, wow, wow, boom!

This appeals to me because I’ve got a bit of a theatrical background.

Think about a James Bond movie, or a stadium concert. The structure might be something like this:

- grand entrance – building excitement, this is going to be good!

- quiet moment, or lesser-known album track

- big action sequence, or greatest hit

- a twist, or set change

- shots of nice scenery, getting from A to B

- a romantic interlude

- a betrayal, or sad song

- another action sequence, or big hit, leading into…

- The grand finale – really knocks your socks off

Those highs and lows aren’t necessarily positive or negative. It’s about the intensity of emotion.

In service design, it’s not usually quite so exciting, but the principle is still true.

Users arrive in a certain state of mind, with certain needs. As designers, we can take care to focus on or pinpoint where these emotional high points are in the story and say, “This is where it really matters.”

You might say, “Well, hold on, Kerrie – it all matters.” In an ideal world, yes, the customer experience would be delightful and polished at every step.

In the real world, pragmatism often applies. If we only have a certain amount of budget and time to invest, what will deliver the best return on investment (ROI)? Where should we start?

Measuring emotions

This is the hard part. The part that requires a lot of creative thinking.

I’d love to say there’s a one-size-fits-all solution but there isn’t. You need to tailor your approach to each project, and each user group.

In brief, though, these approaches are often useful:

- measure the moments that matter

- mix up your measures – don’t just measure one thing

- use ‘social listening’ – monitor social media

- listen to your user communities – respond to feedback, co-create

- consider AI and sentiment analysis tools

- record the customer effort score (CES)

That last one is probably the most effective top-line metric for measuring emotion. Research has shown that it correlates well with customer happiness, probably more so than net promoter scores (NPS).

It asks users for a score of the effort they had to put into using your service.

How do you make people feel?

“I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

That quote, often incorrectly attributed to Maya Angelou, appears repeatedly in management textbooks for a reason.

It’s a neat summary of the importance of emotion, and of the value of improving customer experience.

When people have particularly bad experiences, that becomes a dinner party story you don’t want to be told.

But when they have a good one, they’ll become advocates, selling your product or service to their friends, family and peers.