If you want to bring an innovative product to life, Lean can make it happen. And learning is the fuel that powers its engine.

In our last blog, we talked about how Lean can help organisations do more with less, iterate quickly and get things in front of people.

Lean achieves this by focusing on learning. To make sure a product solves a real-world problem, we need to learn as much as possible as early as possible – about the market, about customers, about people.

We do this by creating a hypothesis. The word comes from Greek, where it means “to suppose”. It’s an assumption, in other words. Not an assumption we rely on, lazily, because we can’t be bothered to do any research. (Designers hate this.) One we test until it breaks or proves to be correct.

For our purposes, hypotheses are instruments you use to prove or disprove an assumption on which your value proposition, business model or strategy builds.

By testing our hypothesis, we stay open-minded to what customers really want and ultimately make something that meets their needs.

In this blog, I’ll discuss:

- where a hypothesis fits into the process of Lean product development

- what a good hypothesis should cover

- how to create a great hypothesis using examples.

Where a hypothesis fits in the lean process and what it should cover

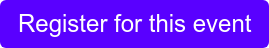

When we carry out Lean product development, we use our SPARCK Learning Loop: rapid, iterative cycles of learning where we take a hypothesis, test it (usually by building something you can put in front of people) and feed what we’ve learned from the results back into the next hypothesis.

You can see how crucial the hypothesis – the assumption we want to test – is to the process. And you’ll also have some idea of how important it is that your hypothesis is a good one.

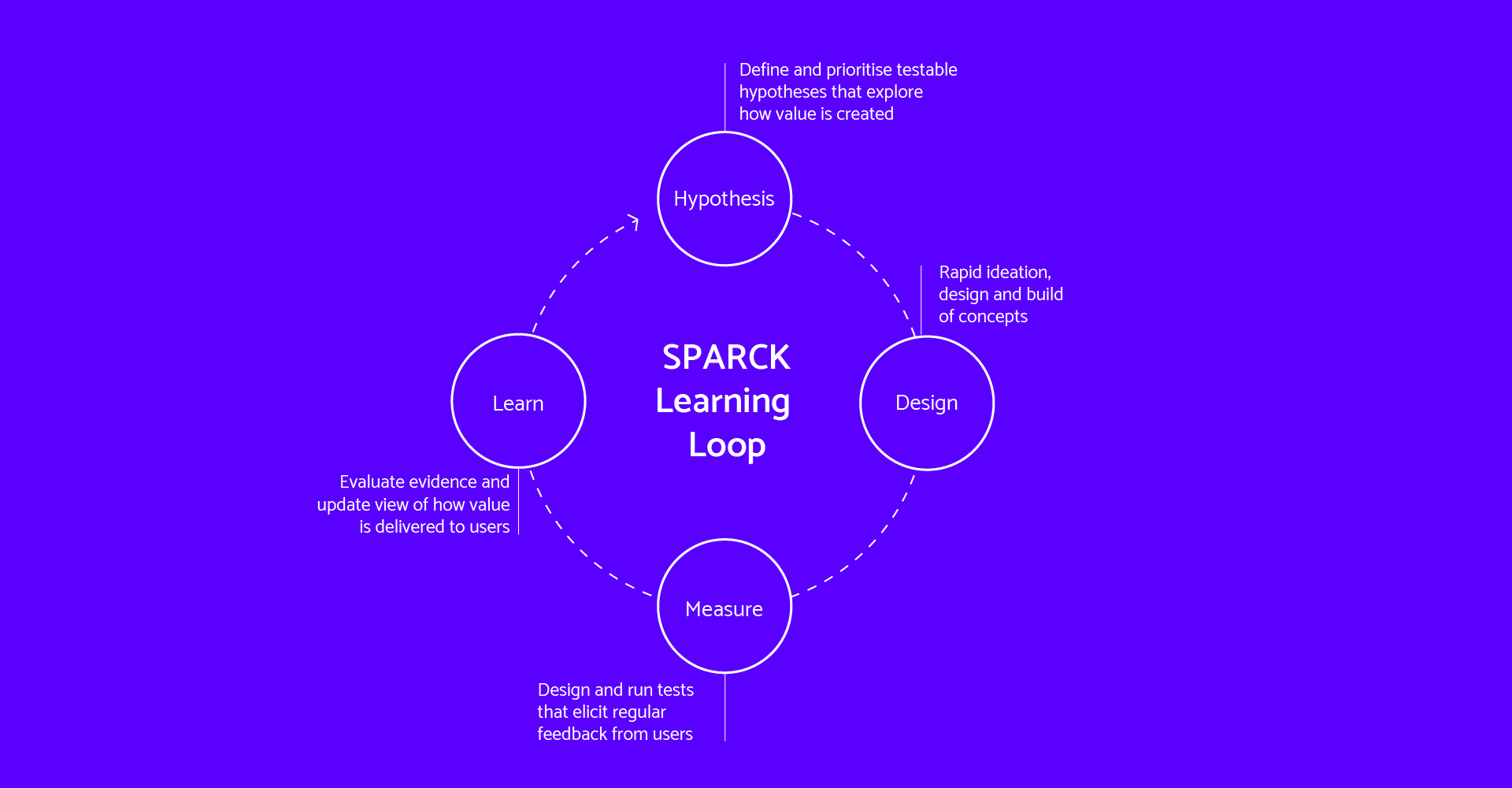

So what should a hypothesis cover? Ideally, it should try to answer a question in one of the three following areas:

- Desirability – Is there a market for this product? Do people want it? Does it offer value to the user? Will people use it repeatedly? Will it be a competitive product? Will people choose it over available alternatives?

- Feasibility – Can we do this? Do we have the right capabilities and culture to deliver the product/service? Can we adequately support and deliver the product/service from an operational perspective?

- Viability – Should we do this? Is it commercially viable? Can we offer the product/service at a cost people are willing to pay? Can we generate enough revenue to cover our costs?

This means you’ll need to do some upfront work assessing the problem space and user needs. Map all your assumptions: what you think you know for sure, what you think is true, and what you would like to be true.

With this done, you’re now ready to start drafting your hypothesis.

How to create a strong hypothesis

A well-formed hypothesis presents an assumption in a way you can investigate through testing. It should be written using this formula:

- We believe that {customers will do the following}

- If this is true it will {create the following business value}

- We will know this is true {when we see this result}

It needs to possess three main characteristics:

Exact – The hypothesis is specific and detailed, describing a clear idea of what success looks like.

- Bad: “Improving the user experience will increase customer retention.”

- Good: “We believe that improving the usability of the payment process will improve customer retention. We will know this is true if users score the ease of use of this process, on average, above 8/10 during testing.”

Testable – The hypothesis can be shown to be true or false. This means that you are clear on what you expect to happen. It should also be possible to test the hypothesis within the boundaries of your work environment in a realistic timeframe and budget.

- Bad: “We believe our client will benefit from Lean methodologies.”

- Good: “We believe our client will reduce cost and time to market for a new product idea when using Lean methodologies. We will know this is true when we successfully launch a Minimum Viable Product in X weeks for £Y and we score an NPS score of above 8 with the client.”

Discrete – The hypothesis describes a single, distinct thing that you want to investigate – not trying to answer multiple questions.

- Bad: “We believe we can generate an increase in revenue through adding personalisation.”

- Good: “We believe we can generate an increase of revenue through adding in-app recommendations. We will know this is true when we see an increase of £X in revenue after Y weeks.”

Once you’ve got all your assumptions in the hypothesis format, you need to categorise them in terms of certainty and impact – how sure you are that they’re true and what will make the biggest difference if true.

You can map these on something like an Uncertainty Matrix, ranking each hypothesis from lowest to highest certainty and lowest to highest impact.

This will help you prioritise. You should take your riskiest hypothesis – lowest certainty and highest impact – to the testing stage. We’ll talk more about testing in the next blog post.

Find out how to put a great hypothesis into action

Formulating a hypothesis is just one aspect of Lean product development – you also need to be able to test it and derive as much insight as possible with the smallest amount of resource.

If you want to know even more about how to put it into action, you can join our upcoming webinar: “The Bare Necessities: How a Lean approach to product development can deliver more value with less work”.

In this free online session, SPARCK’s Alice Kavanagh, Tim Walpole and Raj Lewis will demonstrate how we’ve used rapid cycles of hypothesis-driven learning and experimentation to help clients deliver more value with less work.