You’re probably designing for a mixed language user group right now. Does your content reflect that?

Language should be considered a dimension of accessibility, especially for content that:

- people need to understand quickly and accurately

- gives people access to services they need

- is part of a high-risk process.

Content designers have to consider:

- which varieties of a language people use

- the strategies people use to understand language

- the way people learn an additional language, compared with a home language

- why and how people use the language of your design

- the professional and cultural status of the language

- the higher cognitive load of an additional language, compared with a home language.

Home language and additional language

Our home language is “the first language we learn to speak and is generally the language of our parents and community. Sometimes we can have multiple home languages.” (Kerryn Dixon, Voices Magazine)

Our additional languages are languages we use in addition to our home languages.

Our home language is sometimes called our first language. The description ‘native language’, to mean home language, is becoming less common because of its colonial links.

Our additional languages are sometimes called our second, third or fourth languages.

Understand how people use home and additional languages

Linguistic accessibility is important because people in a group often speak more than one language with various degrees of confidence. People also use different varieties of the same language or create their own variety.

The way a language develops in a multilingual group reflects what people need and want to communicate.

Here are three examples.

1. You are designing a content strategy for a healthcare app available in 100+ countries. It was created in Lagos and the company has a team of 53 based in Lagos and Noida. Most of the employees have 2-3 home languages. They switch between languages depending on who they're communicating with. When the Noida and Lagos teams meet, and when they communicate with partners, they often use English.

2. You are designing a booking and payment service for customers of a catering business in Liverpool. The customers have a variety of home languages and are all based in England. The company uses English as their language of business. All but three of the 27 employees have English as a home language.

3. You are designing an internal social media site for a bank headquartered in Frankfurt. Their 10k+ international employees use English as their language of business. About 5% of the workforce have English as a home language. Everyone has adapted to the workplace's variety of English, which includes Singaporean acronyms and US idioms.

In all three cases, people using your product or service are also using an additional language. You need to think about the most accessible language choices for each group.

And in all three examples, stakeholders in the company will have different – and perhaps strongly held – beliefs about people’s linguistic needs. You need equally strong evidence of people’s linguistic needs to show the value of your design choices.

Build individual language profiles

Here are two examples from past projects, which I’ve anonymised.

Ute is an engineer and company director. Her home languages are German and Turkish. She lives in Munich and works remotely and internationally. She mainly uses English to communicate technical knowledge and strategy with mixed language groups. Her technical vocabulary is accurate and exceeds a lot of home language speakers' knowledge. Her English grammar is limited to simple tenses, which serves her well in most situations, but she feels anxious when using English socially or in new situations.

Abshir is a small business owner. His home languages are Somali and Arabic and he lives in Edinburgh. He does most of his work in person, as well as some remote work with international traders. He uses English and Scots to trade, socialise and do everyday tasks with people who have English and Scots as home languages. His grammar and vocabulary are strong and he rarely struggles or feels stressed when he communicates in English. He needs time or repetition to understand fast-spoken language and complex grammar, especially when multitasking.

Both people are skilled communicators in their additional languages. However, they’ve built different skills based on their needs.

Evidence-led examples like these will help you to:

- empathise with people who will use your design

- challenge your own assumptions

- show how you make design choices.

Challenge assumptions

A few years ago, I surveyed 25 people working in two North African cities. They all used French as a language of business. The group had 13 home languages between them.

These were their answers to two of my questions.

When I communicate in my additional language for 4-8 hours, I am:

- tired

- exhilarated

- eager but temporarily less able to use my home language.

People can help me by:

- speaking at an average pace

- choosing international words (not local words)

- using direct language and sticking to the point

- recognising that I'm working harder than a home language speaker.

These are the lessons I learned:

- Don’t be limited by one standardised language variety when designing a style guide. Instead, research the language varieties and borrowed words people are using

- Keep language clear but don’t assume that additional language users need more simplicity than home language users

- Know that the effects of functioning in an additional language can last beyond the task or interaction

- Challenge assumptions that home language users make about simplicity, directness, and tone.

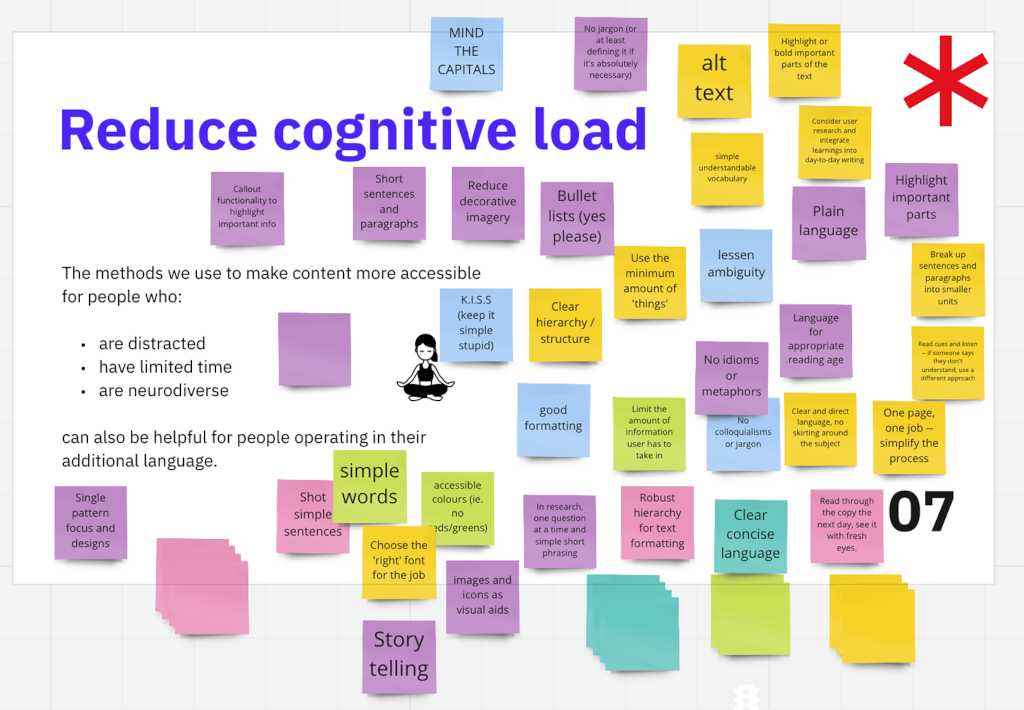

Think of language as a dimension of accessibility

The methods we use to make content more accessible for people who:

- are distracted

- have limited time

- are neurodiverse

can also be helpful for people operating in their additional language.

I recommend brainstorming with your team, then deciding which methods can also apply to linguistically-diverse groups.

Next, here's what we came up with in a brainstorm at SPARCK:

Understand people’s communication strategies

When we read, watch, or listen to content in an additional language, we use strategies to understand.

These strategies are as diverse as we are. But there are some strategies people use frequently.

In another piece of research, I spoke to 15 people based in Asia and Europe. These were the strategies they used in additional languages:

- understand or guess from context

- translate

- observe.

A person might get the meaning of an unknown word from its context. Another person might use an app to translate the same piece of language.

Translation is helpful if we don’t have enough of a language to understand the whole meaning. But translation can be misleading or useless if the language includes local words, phrasal verbs, idioms, or metaphor.

Someone in a public space like a train station, bank or border security queue might observe other people’s actions to fill linguistic gaps.

Research is a good time to learn people’s strategies and use that knowledge to inform your design. I recommend noticing, and noting, your own strategies when you use an additional language.

Quick wins

Here are some quick wins if you’re designing in English language. If you design in another language, tell us about your quick wins in the comments:

- Use direct language (do X) instead of polite language (could you please do X)

- Use single, translatable words (help, assist, progress) instead of phrasal verbs (help out, get on)

- Use translatable words like sick, unwell that are more widely understood across the world instead of idioms like ‘under the weather’ and culturally specific words like ‘poorly’

- Use decipherable words like ‘become angry’ or ‘ambitious’ instead of metaphors like ‘see red’ or ‘stars in his eyes’

- Use meaningful language like ‘work together’, ‘important’ or ‘crucial’ instead of jargon like ‘synergise’ or ‘key’

- Use short sentences instead of long sentences

- Use the simplest grammatical tense possible

- Use the active voice instead of the passive voice.

These quick wins are for guidance.

Content designers make decisions based on lots of evidence, and you might decide that another option works better for the people who use your design.

Wins for the longer term

These suggestions require more time and effort but can deliver sustained results and change in your organisational culture:

- Advocate for diverse research participants

- Advocate for diverse design teams

- Think of linguistic diversity as another dimension of accessibility

- Collect examples of helpful and unhelpful content

- Consider linguistic diversity when designing style guides

- Build language-based profiles and user or job stories

- Test tone of voice on people who have a range of home languages and proficiency in the language of your design

- Understand that language is not only practical: it's deeply rooted in identity and history.